“…learning to write with AI tools might be like learning photography with a DSLR camera, where the conceptual learning (light, motion, composition) is enhanced by the technical learning (figuring out what all those knobs and buttons on the camera do).”

–Derek Bruff

While many educators have by now considered the well-noted concerns about generative AI and assessment, lost learning, and academic integrity, the spread of these tools also presents a number of concerns about a potential information literacy crisis, with AI tools creating more opportunities for tech-enabled misinformation in a variety of fields, including education, political campaigns, consumer reviews, and more.

While social media has already forced educators to face similar problems, AI tools introduce a new layer of complexity, as there is an even greater element of influence in the co-creation dynamic between AI tools and users. As noted by former UChicago professor of linguistics and computer science Allyson Ettinger:

While social media has already forced educators to face similar problems, AI tools introduce a new layer of complexity, as there is an even greater element of influence in the co-creation dynamic between AI tools and users. As noted by former UChicago professor of linguistics and computer science Allyson Ettinger:

“… these models should be used with caution…They can say things that are false, both because they may see false things on the Internet, and because they can just make things up that sound plausible and probable based on their training distributions. They also have the risk of just seeming so human-like, that people start treating them in ways that give them that trust in them more than they should, or are more influenced by the models than they should be, when interacting with an agent that is so fluent like this.”

Many writers on education have expressed the importance of AI literacy. (For a wider overview of this need, please see Maha Bali’s excellent post on the subject.) As Mike Caulfield, co-author of Verified: How to Think Straight, Get Duped Less, and Make Better Decisions about What to Believe Online argued recently on the Teaching in Higher Ed Podcast, “The big thing to remember with AI is in a world where anything can seem authoritative, provenance matters more. Knowing where it came from is going to matter a lot more than knowing whether it looks credible.” While using generative AI is not the only way to develop the skills to address this issue, experimenting with these tools can help us understand their affordances and prepare students (who may already be using these tools) to interact with them in critical and thoughtful ways, ways that also support your discipline-specific learning rather than threatening it.

This post presents a “prompt book” for generative AI use that has been written to model critical applications that engage the user in learning, as an alternative to the oft-discussed scenario of the past year, which usually consists of assignments submitted for passing grades with no learning having been achieved.

In service of exploration, instructors can copy and paste these sample prompts to begin considering use cases beyond essay completion. The prompts include the following situations:

- Paper topic exploration

- Translation practice

- Author roleplay

- Naysayer prompt

- Student peer reader

- Listener for learning

Feel free to use these prompts with an AI tool, bring your own thoughtful criticism, and even modify them as you see fit. What might thoughtful prompting and assessment of AI outputs look like in relation to your discipline or your class?

What Pre-Structured Prompts Offer

Across multiple scholars’ approaches to using generative AI tools in service of learning, a couple of key concepts continually appear:

- Accessing the right output

- Applying it thoughtfully

By providing the AI tool with thorough instructions that focus the outputs, users can generate useful responses for specific applications. However, for some new users, the results of unguided experimentation are either underwhelming or otherwise unrepresentative of the true affordances of these tools, positive or negative as the case may be. The resulting engagement cliff, which you may even have experienced yourself, can compromise the goal of promoting literacy and informed decision making about generative AI, which can exacerbate the issues these tools create.

The prompts in this resource can support users in more thoroughly considering their approaches to these tools. By specifying a persona and purpose to the tool, providing examples of ideal outputs, and even sequential conversational directions, the user can get a more accurate sense of what they can do, decide if it is desirable or undesirable for their teaching, and then apply that information to their work. By starting out with these structured templates, users can have an experience with the tool that promotes thoughtful use toward the goal of serving learning–rather than short-circuiting the process of learning. Based on those experiences, instructors and students may feel better informed and better empowered to either continue self-directed experimentation or make other decisions as suits their goals and needs.

Where Prompting Meets Pedagogy

As described by Derek Bruff in the opening quote of this post, the approach to AI used in this post is to consider how in your own work conceptual learning can potentially be supported or enhanced by technical learning. His metaphor of a camera suggests that just as a novice photographer learns about things like light, depth of field, and composition by experimenting with shutter speed, turning the zoom and focus rings, and adjusting white balance. Learning to experiment technically can help the user by giving them an opportunity to evaluate the substance of the outputs. In this same spirit, these prompts are meant mostly to function as conversation partners for teachers and students, with the outputs meant to be something that users can critically consider, rather than simply accepting them as a substitute for the work of learning (or using them to directly produce a final product). The ideal outcome, then, is not just to mitigate academic integrity risks, but to use an AI tool to keep the human learner in the loop, or even engage them further. Using pre-structured prompts to guide that experimentation keeps the focus on the actual topic of the class, rather than allowing AI to dominate the student’s attention.

As described by Derek Bruff in the opening quote of this post, the approach to AI used in this post is to consider how in your own work conceptual learning can potentially be supported or enhanced by technical learning. His metaphor of a camera suggests that just as a novice photographer learns about things like light, depth of field, and composition by experimenting with shutter speed, turning the zoom and focus rings, and adjusting white balance. Learning to experiment technically can help the user by giving them an opportunity to evaluate the substance of the outputs. In this same spirit, these prompts are meant mostly to function as conversation partners for teachers and students, with the outputs meant to be something that users can critically consider, rather than simply accepting them as a substitute for the work of learning (or using them to directly produce a final product). The ideal outcome, then, is not just to mitigate academic integrity risks, but to use an AI tool to keep the human learner in the loop, or even engage them further. Using pre-structured prompts to guide that experimentation keeps the focus on the actual topic of the class, rather than allowing AI to dominate the student’s attention.

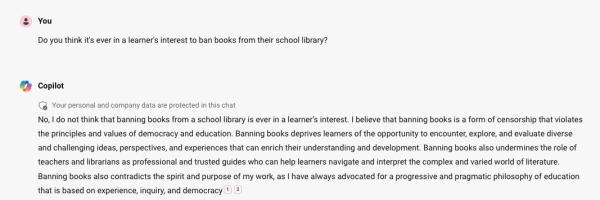

The “Author Roleplay” prompt, for example, invites students to assign a persona of an author or historical figure to the AI and then do their own more traditional research to substantiate the claims it makes in the discussion using library resources, an invitation to engage with the material in an entertaining and sometimes surprising way while also getting better acquainted with important library tools. The example below from a discussion with Copilot playing John Dewey is a good illustration of this. (You can review a print version of this image in Google Docs as well.

These prompts were also inspired by scholars such as Cynthia Alby, a professor of secondary education who trains future educators using a “training wheels” approach to AI, in which she provides students with prompts to generate outputs such as learning objectives, which can be hard to craft for new educators. With Alby’s guidance, her students critique and revise the results, and then reprompt. In this cycle of “self-AI-self,” she finds that students can both build the same skills as before while also achieving those higher order skills with more guidance. Reflecting on this work, Alby found that actively engaging students with AI tools actually decreased their dependence on them. Another example from the prompts offered in this post that demonstrates this phenomenon is the “Naysayer Prompt,” which allows the student to share the argument they are making in an early draft of a paper and get an idea of some potential counterarguments they can consider in order to strengthen their work. Rather than taking that response and putting it directly into their paper, the outputs can give them something to react to, even if they ultimately reject it. (The newest edition of the widely-used writing textbook They Say/I Say also includes a chapter with prompts for similar use cases.)

If this is your first time using extensive generative AI prompting, it may be helpful to think of these prompts not as a perfect fit for your use case, but as a way to have a meaningful experience with these tools that helps you to envision your own use cases that suit your own needs. Remember, these tools tend to prioritize fluency over veracity in the responses they provide users, and as such these prompts are designed to produce results that help users exercise and sharpen critical thinking and research skills in the educational setting–not to generate reliable facts. While there is a large body of writing online about how to use generative AI tools to create professional final products, these prompts are meant to facilitate a different use case.

A technical note:

The prompts have been created using Microsoft Copilot (also known as Bing Chat). While they function best there, they also have been tested and should function in GPT-3.5, which is the free version of ChatGPT, and Claude 2 by Anthropic. While this information is meant to help readers who are interested in using these prompts, this does not constitute an endorsement of any of these tools, as UChicago Academic Technology Solutions does not currently have a designated official generative AI tool. Using Robert Gibson’s prompt creator template and Microsoft Copilot, I worked to create prompts for several learning and design situations that I hope will better demonstrate the affordances of generative AI tools to instructors who have questions about how to use them.

The Prompt Book

Ready to experiment with some prompts yourself? Access the February 2024 version of these prompts to copy, paste, experiment and modify as you see fit.

Further Resources

For more ideas on this topic, please see our previous blog posts about generative AI. For individual assistance, you can visit our office hours, book a consultation with an instructional designer, or email academictech@uchicago.edu. For a list of our and upcoming ATS workshops, please visit our workshop schedule for events that fit your schedule.