Mind-mapping tools allow the user to organize multiple items of information in the form of a map or web, visualizing relationships and making connections between data. George Adams, a doctoral candidate in Music and fellow with the Chicago Center for Teaching (CCT), employed one such mind-mapping tool in the course Music in Western Civilization, for which he served as a teaching assistant in Spring Quarter 2019, in order to help his students think through the course material in new ways and discover relationships they might not have imagined before.

The Problem

In Adams’s discussion section, held once a week for 50 minutes with a class size of 10, students were asked to engage closely with secondary source readings and draw upon them to illuminate particular pieces of music, such as Brahms’ Violin Concerto in D Minor or Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Adams found that his students were sometimes grappling with a tendency to create rigid genre binaries, such as Classical vs. Romantic music, as a result of the secondary sources’ representing the course material in terms of neatly defined, clearly distinct categories.

The Choice of Tool

To help combat this tendency and break down the walls between categories, Adams sought a tool that was well suited to depicting webs of connections in graphical format. He was already familiar with a mind-mapping tool called Lucidchart, having explored it in workshops held jointly by Academic Technology Solutions and CCT, and decided early on in the quarter to introduce it to his students at some point. Like most mind-mapping tools, it had a relatively easy learning curve, which made it ideal for his purposes.

The Exercise

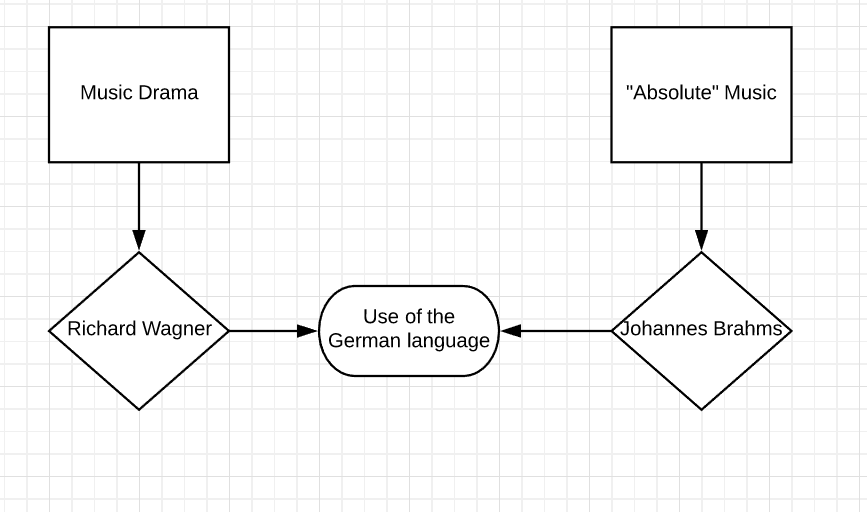

Adams’s mind-mapping exercise was carried out in Week 7 of Spring Quarter, in conjunction with a discussion of Romanticism in music and art. Adams began by setting up approximately half the framework of the chart, then invited his students, working collaboratively as a group, to think of new connections between items on the chart and join them. He took pains to stress that the exercise was low-stakes, and that his students should feel free to express themselves without worrying about making mistakes. The map that resulted from the students’ collaboration showed surprising links between figures and concepts the students had previously envisioned as separate — e.g. Wagner and Brahms, who are commonly portrayed as antitheses in terms of their musical styles, but who shared influences from 19th-century German nationalism.

An example mind map created in Lucidchart, showing how the use of the German language in their vocal music connects Wagner and Brahms

The Results

Although the mind-mapping exercise was a one-time exercise, it brought together ideas that had been introduced over time since the beginning of the course, and so served as a summative exercise to help Adams’s students re-frame the material they had been presented with, in preparation for writing their second course paper. Adams was pleased with the outcome of the exercise; he felt that it helped the students to break out of the box of categorization and make new associations that deepened their historical thinking. This sort of free association, he believes, is immensely valuable for introducing students to the complex thought processes necessary to produce strong historical scholarship.

Impact and Lessons for the Future

Adams advises others who are interested in using mind-mapping software to introduce their chosen tool as early as possible. This way students will already be familiar with the tool and ready to use it at the point at which you have integrated the tool into your lesson plan.

Adams was so pleased with the success of his exercise that he is already planning future ways to integrate mind mapping into his pedagogy. He encouraged his students to pursue mind mapping on their own and then build their arguments upon it in their second course paper, as a way to stimulate outside-the-box thinking. He welcomes faculty and instructors to give mind mapping a try and see how it may be able to enhance their own classroom pedagogy.

Using Collaborative Mind-Mapping Tools

To learn more about LucidChart, one of the most feature-rich collaborative mind-mapping tools available today, see The Beginner’s Guide to Lucidchart. For those seeking an alternative free tool, draw.io is robust and allows you to create basic mind maps easily and save them to Google Drive, Microsoft OneDrive, or your local device. You can also work collaboratively on a mind map in draw.io by sharing it in Google Drive.

Getting Help

For one-on-one help with using mind-mapping software and other academic technologies, or if you have other questions, please contact Academic Technology Solutions.