Author’s Note: This is the latest installment in an ongoing series of articles about issues pertaining to academic integrity in higher education. For earlier installments, please see: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

ATS instructional designers Mohammad Ahmed and Michael Hernandez contributed content to this article.

- Introduction

- The State of the Tool

- Issues for Academic Integrity

- How Do We Deal with the Problem?

- Further Resources

Introduction

There are few current issues in education that have provoked more interest – or sounded more alarms – than artificial intelligence (AI) technology. While the issue has simmered for some time, it burst into the forefront of debate following OpenAI’s public release of ChatGPT. When given a prompt – e.g. “What were the causes of World War I?” or “How does the Krebs cycle work?” – ChatGPT (the acronym stands for “Generative Pretrained Transformer”) can generate text that reads, at least on superficial examination, like that written by a human – the basis of the famed Turing Test for machine intelligence.

Once the tool’s capabilities became known, it did not take long for fears to be voiced that students would turn to ChatGPT to write their assignments for them. Eye-grabbing headlines began to appear, not only in sensationalist newspapers like the New York Post (which dubbed the tool “CheatGPT”) but in more sober publications like the Atlantic, where an opinion piece bluntly claimed that “the college essay is dead”. Advocates for the worst-case scenario see a future in which human-generated and computer-generated text are indistinguishable, essay assignments are meaningless, and the very skill of academic writing is lost.

One need not accept this doomsday proposition to recognize that ChatGPT raises legitimate concerns for academic integrity. But if we are to address such concerns, we must first answer several key questions: what is ChatGPT, exactly? What are its affordances and limitations? And, assuming that ChatGPT and tools like it are here to stay (as seems overwhelmingly likely), how should we rethink pedagogy to address this new reality?

The State of the Tool

At this time, ChatGPT is essentially an information aggregator. It trawls vast quantities of human-produced texts and extracts data, which it then synthesizes into a response to a given prompt. As noted above, its responses on many topics are at least coherent enough that they may be superficially indistinguishable from student writing.

As with all AI tools, though, ChatGPT’s capacity to give responses depends upon what, and how much, it is “fed”. Its lack of data on current events, for example, limits its capacity to respond to prompts such as “How is the war in Ukraine progressing today?” There are also guardrails in place to prevent the tool’s being used for nefarious purposes (though cybercriminals are already seeking to circumvent these).

There are other significant limitations to the tool as well. It cannot cite sources correctly – any request for a bibliography produces false and/or irrelevant citations. Nor is it error-free: users have run across blatant, even comical, mistakes when ChatGPT is asked a question as straightforward as “How do you work?” Like all AI, it is subject to the biases of those who supply its data. And, most fundamentally, it is not true artificial intelligence. There are no indications that ChatGPT understands the questions it is being asked or what it is producing in answer; simply put, it is not sapient. This is worth keeping in mind as the debate rages over whether such tools are capable of supplanting human creativity.

Issues for Academic Integrity

It is, without question, too early in the game to expound upon all the possible difficulties ChatGPT and similar generative AI tools could pose for academic integrity. Already, however, ChatGPT-generated text has proved itself capable of evading plagiarism checkers such as Turnitin. Plagiarism detection software relies on comparing student work to a database of pre-existing work and identifying identical phrases, sentences, etc. to produce an “originality score”. Because the text generated by ChatGPT is (in some sense, anyway) “original,” it renders this technique useless.

ChatGPT also ties into the broader issue of contract cheating – hiring a third party to do work, such as writing an essay or taking an exam, on a student’s behalf. Contract cheating is already a severe problem worldwide, and with the widespread availability of AI writing tools, students can now generate “original” written work for free, without the need to involve a human agent who might betray the student’s confidence.

How Do We Deal with the Problem?

As the New York Times has noted, many faculty and instructors already feel the need to adjust their pedagogy to account for the existence of ChatGPT. Their strategies, actual and proposed, for coping with the tool can be divided into three categories: technological prevention; non-technological prevention; and creative adaptation. We shall consider each of these in turn below.

Technological Prevention

It will come as no surprise that technological counters to ChatGPT are already in play. A 22-year-old computer science student at Princeton named Edward Tian has introduced GPTZero, which claims to distinguish human- and computer-generated text with a high degree of accuracy. Meanwhile, other plagiarism tools, such as Turnitin, offer their own AI-detection tools and are rapidly working to detect the newest generation of generative AI text. And finally, the makers of ChatGPT are themselves exploring “watermarking” technology to indicate when a document has been generated by the software.

Some experts foresee an “arms race” between AI writing tools and AI detection tools. If this scenario comes to pass, faculty and instructors will be hard-pressed to keep up with the bleeding-edge software needed to counter the newest writing tools. But more fundamentally, we might ask: is technology always the best solution to the problems it creates? Or are there other, perhaps less involved, means of addressing the questions raised by AI?

Non-Technological Prevention

At the other end of the spectrum, some faculty and instructors have sought to neutralize ChatGPT entirely. This may entail banning ChatGPT specifically; banning all computers in the classroom; supervising student essay-writing, whether in class or via monitoring software such as Proctorio; or even requiring writing assignments to be handwritten.

The concern that underlies such measures is understandable, and they can be effective in the short-term, but they come at a cost: aside from the anxiety that can be provoked by being under surveillance, accessibility issues that may be raised by requiring handwritten work, and the legal/ethical issues raised by video proctoring, students miss the opportunity to learn about the tool and its implications. As we confront the likelihood of a future with ubiquitous AI technology, those students who have never experienced tools like ChatGPT and who know nothing about their uses may well find themselves at a professional disadvantage.

Creative Adaptation

At this point in time, it seems most productive to take a third path – one that balances the need to safeguard academic integrity with the reality that ChatGPT and its like are here to stay. Here are some suggestions for methods to integrate AI tools like ChatGPT into your pedagogy in a productive, rather than destructive, fashion.

- Clarify expectations at the outset. As early in your course as possible – ideally within the syllabus itself – you should specify whether, and under what circumstances, the use of AI tools is permissible. It may help to think of ChatGPT as similar to peer assistance, group work, or outside tutoring: in all these cases, your students should understand where the boundaries lie, when help is permissible, and when they must rely on their own resources. You might also discuss with your students how they feel about AI and its ability (or lack thereof) to convey their ideas. Emergent research suggests that at least some students feel dissatisfied with the results when they entrust expression of their ideas to AI.

- Craft writing prompts that require creative thought. A tool like ChatGPT can easily respond to a simple prompt such as “What are the causes of inflation?”, but it is likely to have trouble with a prompt such as “Compare and contrast inflation in the present-day American economy with that in the late 1970s”. The more in-depth and thought out the prompt, the more it will demand critical reasoning – not simply regurgitation – to answer.

- Run your prompts through ChatGPT. Related to the point above, actually using ChatGPT on a draft of your writing prompt can be an illuminating exercise. Successive iterations may help you to clarify your thinking and add nuances to your prompt that were not present in the initial draft.

- Scaffold your writing assignments. This is a time-honored technique for combating plagiarism of any kind in academic writing. It will be much harder for a student to submit a final draft generated by AI and get away with it if you have observed that student’s thinking and writing process throughout the course.

- Promote library resources. As mentioned previously, ChatGPT is not presently able to generate an accurate bibliography, nor does it understand the concept of citation. This shortcoming can be a good jumping-off point for you to explain to your students how to cite properly, why citation is important, and how they can use available resources to do their own research.

- Model productive use of AI tools. For all its hazards, ChatGPT also offers promising possibilities. A “dialogue” between the user and the tool can help the user to probe deeper into the subject matter, become familiar with mainstream scholarship on the topic, and push beyond “easy answers” toward original work. To promote such dialogue, you might, for example, assign your students to come up with their own prompts, post them to ChatGPT, and then comment on the answers, finding the strengths and weaknesses of the “argument” that the tool generates.

In a field evolving by the day, no article, this one included, can hope to offer definite answers. What we have presented here are points we hope will contextualize the debate and provide a framework for further discussion. In the end, what AI tools will mean for higher education – and for society as a whole – remains to be seen.

Further Resources

To learn more about AI in the classroom, we recommend the excellent page on AI Guidance from Yale’s Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning. Turnitin also offers a concise but helpful Guide for approaching AI-generated text in your classroom.

If you have further questions, Academic Technology Solutions is here to help. You can schedule a consultation with us or drop by our office hours (virtual and in-person, no appointment needed). We also offer a range of workshops on topics in teaching with technology.

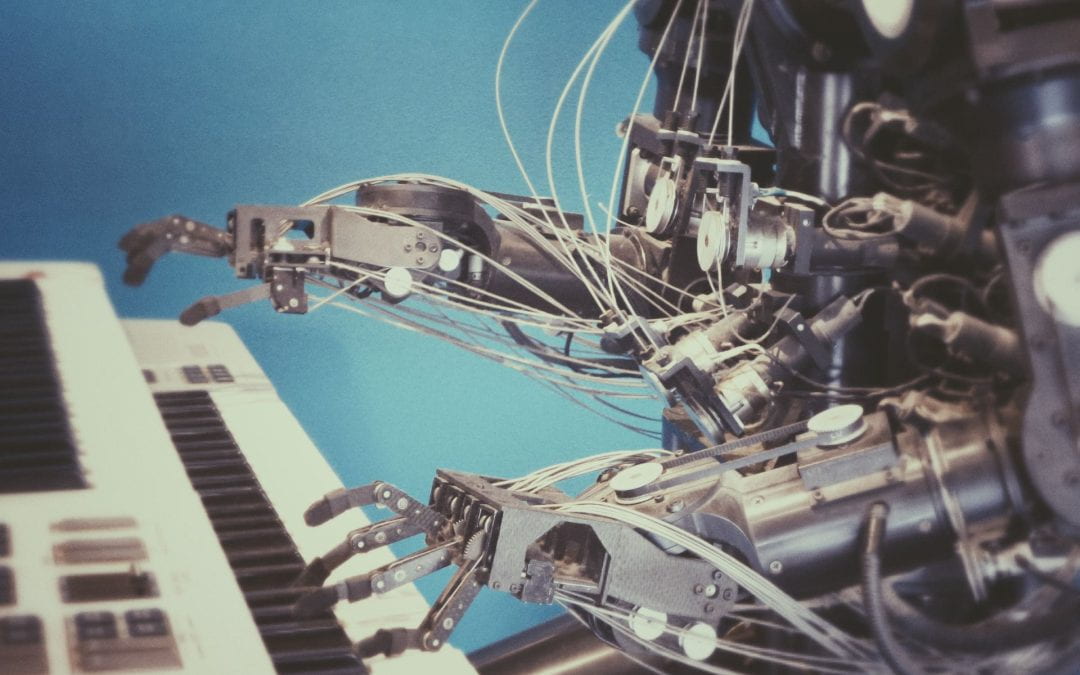

(Cover Photo by Possessed Photography on Unsplash)