This three-part series explores a wide range of digital tools and pedagogical strategies that support writing instruction. Over these three posts, we will consider a diverse array of writing-related goals and instructional contexts from across the disciplines. This first post offers an approach to writing – and to writing instruction – as a process; the second and third posts explore specific digital tools suited to two stages of the writing process: development and drafting, and workshop and revision, respectively. For a deeper engagement with the topics, strategies, and tools featured in this series, consider registering for the upcoming ATS workshop Digital Tools for Teaching Writing, offered on October 23 from 1:30-2:30 pm (register) and November 2nd, from 11 am – 12 pm (register).

In the diverse and shifting landscape of contemporary higher education, writing occupies an essential – though often highly fraught – place. At the same time that writing represents the cornerstone of academic work (as both the conduit through which new research contributions are offered and the site of original scholarly and pedagogical interventions in itself), institutions handle the teaching of writing in divergent ways. Whereas some universities emphasize first-year composition as a crucial gateway experience for new undergraduates, others forego composition instruction as such in favor of “writing-intensive” courses or discipline-specific writing seminars. And whereas some students arrive in undergraduate or graduate programs with extensive writing experience beyond that of the so-called “five-paragraph essay,” many others do not. As a result, writing is often a site at which myths of individual academic genius are mobilized in implicit or explicit ways. As one refrain – ungenerous and, as we shall see, untrue – would have it: “Students either get it or they don’t.” The insidious implication? Writing can’t be taught.

With access to artificial intelligence (AI) tools on the rise, developing a robust approach to writing instruction feels, for many instructors, newly urgent. How can faculty foster rigorous and transformative writing experiences if, allegedly, “all” students in this brave new world are using LLM (large-language model) tools to generate their prose? Yet at the same time that instructor anxiety around writing has reached a new tenor with increased access to AI tools, Jacob Babb reminds us that there is nothing new about hand-wringing over student writing. As he writes in a contribution to the 2017 collection Bad Ideas About Writing (eds. Cheryl E. Ball & Drew M. Loewe, West Virginia University Libraries): “The notion that literacy is in crisis is nothing new.” Citing a Newsweek article from 1975 “entitled ‘Why Johnny Can’t Write,’” Babb describes an alarmed author who worries “that technologies such as computer printouts and the conference call were destroying Americans’ abilities to produce clear and concise prose in professional settings” (13). While LLMs and conference calls open onto, of course, very different practical concerns (not to mention affective responses of wildly different scales), Babb offers us a helpful reminder: emerging technologies have an uncanny way of throwing longstanding concerns into a new light.

This blog post proposes a different orientation to writing and to the teaching of writing – one that is attuned to process rather than product and that emphasizes the ongoing transformation of students’ writing over their starting points or previous experiences. Such a shift in mindset might sound basic: How, instead of bringing a hyperfocus to bear on the final outcomes of student writing (e.g. a polished term paper), might we as instructors widen our view to consider the parts and pieces, the practices and rehearsals, that students will pursue on the way there? This shift in perspective, moreover, might sound familiar, as it is part and parcel with a pedagogical approach grounded in backwards design and constructive alignment – two principles that emphasize a purposeful and iterative approach to the design of assignments, assessments, and learning objectives. As we shall explore in this post and in subsequent installments in the series, a thoughtful use of academic technology tools can be invaluable in process orientation to writing instruction rooted in iterability, revision, and practice.

Writing and/as Process

The notion that writing “is a process” is something of a commonplace – but in this post, we treat the idea of process as more than a metaphor. While, for example, it rings true that the process of writing is centrally about “the journey as much as or more than the destination” (as the cliché runs), this risks overlooking the fact that writing is where thinking occurs. In other words, writing doesn’t merely deliver a final destination; much more foundationally, it generates the condition of possibility for thought and the exchange of thoughts. As Kerry Ann Rockquemore of the National Center for Faculty Development and Diversity puts it, writing “IS thinking.” Or, as Eric Hayot opens his popular monograph The Elements of Academic Style: Writing for the Humanities (Columbia University Press, 2014): “Writing is not the memorialization of ideas. Writing distills, crafts, and pressure-tests ideas – it creates ideas” (1). Concurrently, the practice of writing – the incremental, iterative, gradual, and recursive work of keeping going in language – produces myriad transformations in the writer. Instead of passing by mile markers on the way to a completed essay, a writer transforms over the course of the process (9).

By attending to process in the design of our writing assignments, we challenge our students to use writing in two complementary ways: by writing to learn (WTL) and by writing to show learning (WTSL). In the framework of WTL, students generate writing to discover their points of curiosity and interest, to identify “gaps in the literature” or unanswered questions, to understand their own intuitions (i.e. what is it about this poem that makes me think x?), and to work generatively toward an idea or argument. In the framework of WTSL, students make a shift, attuning themselves to their imagined audiences and recalibrating their ideas and evidence accordingly. As these two frameworks and their respective goals indicate, no writing project can encapsulate the entirety of a writers’ thoughts and ideas – nor can it address itself to every audience imaginable. By toggling between these frameworks, however, students become more reflective practitioners, equally capable of using writing as a tool for thinking and as an instrument of communication.

Emphasizing the importance of process and practice in the context of writing has a significant impact for students and instructors alike. For one, from the standpoint of transparency, equity, and accessibility, approaching writing as a process makes a simple but powerful claim: No one “just knows” how to write! In focusing on process, we make our expectations for student work transparent and empower all students to realize their writing goals. Additionally, emphasizing process is one of the most effective ways to bolster academic integrity in the classroom. When students approach a writing assignment incrementally, they take ownership of their own thoughts, research, and prose from the outset. As they move forward in the process of work toward a large-scale project, they sharpen concrete skills that support ethical research and writing practice. And, more foundationally, when students build their own ideas from the ground up, they undertake a task that no LLM could do in their stead.

Academic Technologies and Process

Pivoting from an outcome-oriented approach to writing instruction to a process-grounded orientation is a big transition. Academic technologies and digital tools can be powerful stewards of process when working toward this change. When revamping a writing assignment, you might ask yourself the following pair of questions:

- What steps would a student encountering this genre of writing for the first time need to move through in order to complete it?

- What tools will help students complete these steps and enable me to provide feedback as they proceed?

When we approach writing only through its final products, like a revised research paper or glossy scientific poster, all of the materials students generate along the way disappear from view. Digital tools have a unique capacity to capture some of these ephemeral drafts, part-ideas, and sketches; moreover, digital tools offer instructors a window of opportunity to provide formative feedback to students. Consider how an assignment as simple and routine as a weekly response post on a Canvas discussion board transforms through a process orientation and the strategic use of digital tools.

Assignment: Write a Canvas post of 400 words in which you identify a concept from The Interpretation of Dreams that is new to you, connect that concept to the Alice Munro story we read last week, and speculate on how the concept connects to your everyday life.

- Task: Close reading

- Overview: Student engages closely with theoretical text to identify concept

- Digital tools: Student makes use of annotation features (Canvas; Hypothes.is) to mark up their copy of the text

- Task: Identify a concept

- Overview: Student sifts through their notes and annotations to pinpoint and explain a specific idea

- Digital tools: Student engages in social annotation (Hypothes.is), refers back to class lecture slides and notes (Canvas; Panopto), makes quick searches for context (Google; Wikipedia; library databases)

- Task: Connect concept to short story

- Overview: Student rereads short story, marks up text, returns to discussion notes

- Digital tools: Personal notes (tablet; laptop); class notes (Canvas)

- Task: Connect concept to everyday life

- Overview: Student brainstorms, reflects, gathers points of connection

- Digital tools: Personal communications (phone; social media); personal digital archives (emails; web browsing history); mediated events (Zoom lectures; talks; concerts; social events)

- Task: Write 400-word post

- Overview: Student synthesizes everything they’ve generated and addresses audience of their classmates

- Digital tools: All of the above; discussion board (Canvas); composition tools (Google Docs, Word, Pages); brainstorming tools (pen and paper; Jamboard); AI tools, depending on course policies; revision tools (Grammarly)

In completing this low-stakes assignment, students move through an impressive number of interpretive and compositional tasks. Along the way, digital tools help in powerful ways: enabling a student to create a dedicated space for brainstorming; opening up a digital conversation between peers through social annotation; pointing students toward everyday archives of non-traditional sources; supporting students’ diverse approaches to note-taking, drafting, and editing; and more.

In subsequent installments to this series, we will consider some specific scenarios and strategies for reconceptualizing large- and small-scale writing projects through the lens of discrete steps, skills, and practices. The next post will consider strategies tailored to the drafting and development of writing projects, while the third and final post will explore strategies for revision and feedback.

Read Digital Tools for Teaching Writing, Part 2: Development and Drafting and Digital Tools for Teaching Writing, Part 3: Workshop, Feedback, and Revision for more.

References

- Cheryl E. Ball & Drew M. Loewe, eds., Bad Ideas About Writing (Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Libraries, 2017).

- Chicago Center for Teaching and Learning (CCTL), University of Chicago, “Assignments.”

- Chicago Center for Teaching and Learning (CCTL), University of Chicago, “Course Design.”

- Elizabeth Guzik, “Problems with the Five Paragraph Essay,” California State University – Long Beach Writing.

- Eric Hayot, The Elements of Academic Style: Writing for the Humanities (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014).

- Kerry Ann Rockquemore, “Writing IS Thinking,” Inside Higher Ed, 18 July 2010.

- Owen Kichizo Terry, “I’m a Student. You Have No Idea How Much We’re Using ChatGPT,” Chronicle of Higher Ed, 12 May 2023.

Image Credits

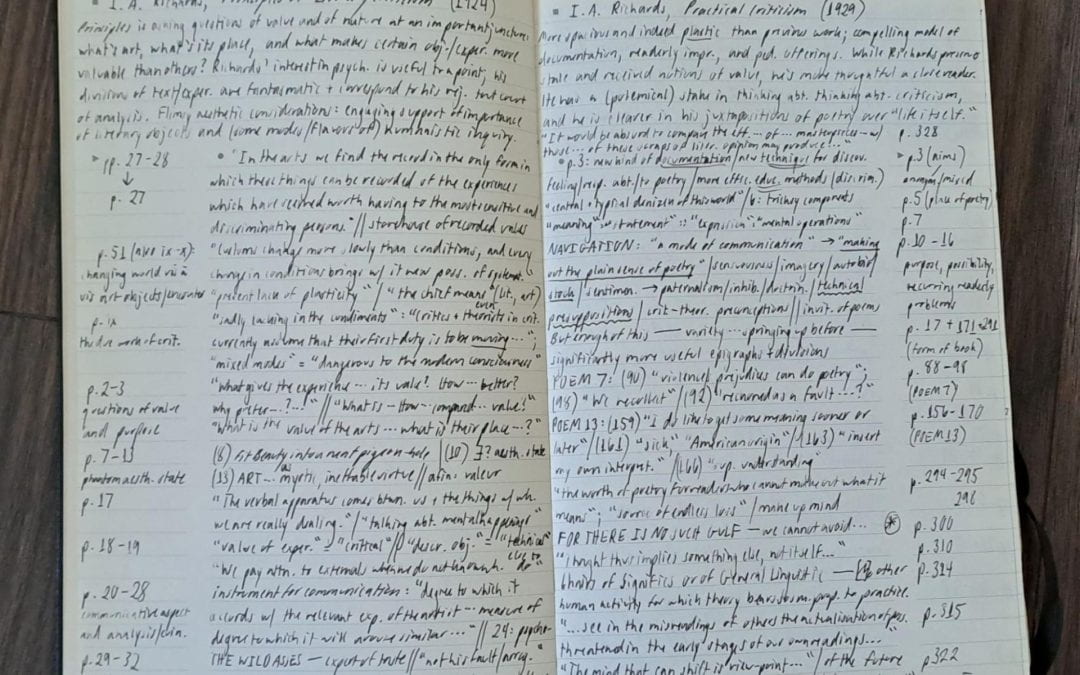

Image by author.