This post is part of an ongoing series to promote active learning strategies and teaching tools that can support instructors in using them. Active learning is an area of particular interest on the UChicago campus this year, with the Chicago Center for Teaching and Learning hosting a Symposium on Active Learning Strategies on April 13, 2023 and Academic Technology Solutions (ATS) hosting the new active learning series Try IT: Academic Tech for Active Learning. See the ATS calendar for a full list of topics and specific dates.

What is an active learning exercise?

Descriptions of active learning often start with what it is not: passive receipt of information through traditional lectures. However, since Bonwell and Eison published the first book dedicated to active learning in 1991, educators have been creating and refining many more specific and diverse ways of engaging students in constructing knowledge with a combination of problem-solving, collaboration, and metacognition. You can find an even more exhaustive list in the Vanderbilt Center for Teaching’s handout on active learning, but Handelsman et al. provide an excellent list for educators to start with in their acclaimed book Scientific Teaching, which includes:

- group problem solving

- electronic audience response systems

- brainstorming, one-minute questions

- “strip sequence”

- decision making

- concept mapping

- “mini-maps”

- case- and problem-based learning (Handelsman, Miller, and Pfund 2007, 30-33)

Many faculty and instructors will notice that the broad category of active learning includes familiar practices that they have already tried in some form as a means of engaging students and collecting useful updates on their progress, from clicker poll questions to simple brainstorming exercises. As described in a 2011 report published in Science, when researchers in physics education compared courses that employed traditional lecture only with those that employed constructivist approaches including pre-class reading and quizzes, clicker questions, student discussion, and small-group work, they found better results from the classes using active learning approaches by metrics of attendance, engagement, and achievement (Deslauriers, Schelew, and Wieman 2011).

So, now that we’ve reviewed both the premise and the promise of active learning, we’ll turn to a breakdown of how you can use active learning and how UChicago teaching tools can help.

Choose Your Topic

In order to make your activity as effective as possible, it’s important to select a discrete topic or concept that your active learning exercise will address. (This will be especially helpful if you plan on pairing the activity with a microlecture, which calls for smaller chunks of material in order to create more significant learning.) If you’re having trouble selecting the concept you want to focus on, you’ll find that the key to this is well-stated by Handelsman et al in Scientific Teaching:

“An essential element of active learning exercises is to choose the most important or difficult concepts as the focus for an exercise. In designing active exercises, it helps to remember that every scientific fact was once a question, so anything in science can form the basis for active, inquiry-based learning.” (Handelsman, Miller, and Pfund 2007, 27)

Even outside of the sciences, if you’re not sure where to start, you might consider an activity that invites your students to try one of the following:

- reconstruct a foundational idea that is now taken for granted

- build on knowledge you’ve just introduced

- apply a concept to better understand how it works

From there, you may see a natural use for practices like reflective writing in minute papers, close reading of and response to a case study, a role play with a classmate, or even just a few quick poll questions to check for understanding.

Choose the Exercise that Works for Your Objective

Below you’ll find an overview of active learning exercises you can create using UChicago teaching tools (all of which you can learn more about in our active learning series Try IT: Academic Tech for Active Learning.)

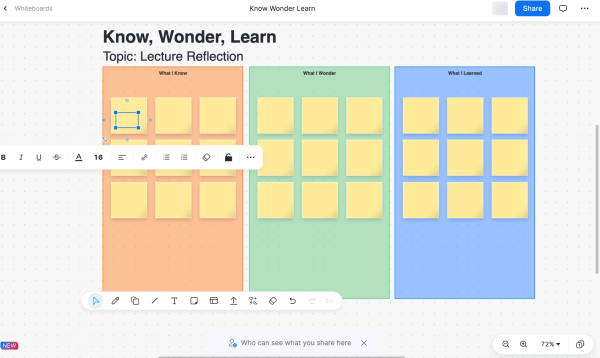

Use Whiteboards to Create Opportunities for Collaboration, Idea Generation, and Non-Linear Interaction with Concepts

ATS can offer instructors support with using both Google Jamboards and Zoom Whiteboards, similar tools that will allow you to create activities with varying degrees of structure. Such activities have become popular in recent years for icebreaker activities, but with a small amount of setup ahead of time, you can also use them to engage students in concept mapping or strip sequence activities. They can even be used for simple brainstorming activities with classmates. (Pictured above you can find one of the many templates provided by Zoom, which instructors can modify instead of building from scratch.)

- Strip sequences: Popularized by Handelsman, a strip sequence asks students to work together to take a series of events you’ve presented them with and place them in the correct order. While originally designed for learning biological processes, this method could be employed for other subjects as well.

- Concept maps or “mini-maps”: Handelsman also recommends this activity, which asks students to arrange concepts spatially to represent their relationships in the absence of a linear or causal relationship. Again, while originally presented as an aid for learning biological concepts, there are clear uses for this activity outside of science, like laying out the scholarly conversation between course readings.

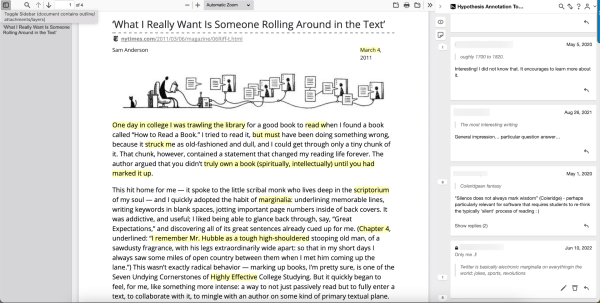

Bring Students Together Over Course Reading Using Hypothesis

Social annotation activities ask students to take an active role in course reading rather than passively receiving information. You can assign your students specific tasks like questioning, providing context from other resources, summarizing for their classmates, and more. Students will also be able to respond to one another as they annotate documents like journal articles, case studies, or even your lecture notes.

If you’re not sure where annotation fits into your course or your discipline, consider the five affordances of annotation, described in the recent book Annotation from MIT Press, to help you communicate to students what you consider a meaningful annotation:

- Providing information: The work of providing context can help the annotator and make the text more accessible for others. Students can be prompted to research, define, and elaborate on ideas in the text, even bringing in links to outside sources when relevant.

- Sharing commentary: This form of annotation can include the dissent to or endorsement of other opinions, denoted by likes, downvotes, emoji reactions, and more. It can also include the use of a hashtag to organize or associate an excerpt with a larger discussion.

- Sparking conversation: The act of thoughtful dialogue in the margins has the potential to bring more life to the text. What starts as a reply to the author can become a spirited debate among readers. Encouraging the use of threaded replies and multiple modalities can also support self-sustaining and substantial conversation.

- Expressing and questioning power: Deliberately questioning the text and providing counterpoints can help bring our reading past the level of summarizing, rephrasing, or noting core ideas.

- Aiding learning: As preparation for discussion, you may be interested in providing your own annotations and then inviting your students to interact with them. A demonstration of your own interaction with the text may help model future reading. (Kalir and Garcia 2021)

To get started with Hypothesis, see our knowledge base article.

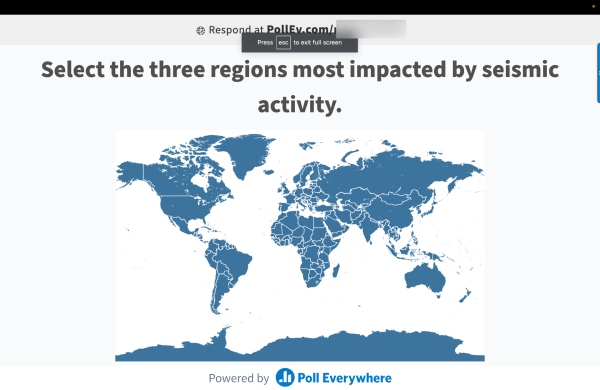

See What Concepts are Clicking with Your Students Using Poll Everywhere

Often used for checks for understanding like “muddiest point,” clickers or poll software can provide a great complement to short lectures you’ve decided to deliver live, rather than as a recording. Some instructors also find that the retrieval practice of regular quizzing helps concepts stick better in the students’ memories. Clicker polls can help you collect important data on your students’ current needs and even prompt more in-depth discussions based on the results.

Using Poll Everywhere, an instant polling software tool supported by UChicago, you can administer question types like short answer, multiple choice, image hotspots, and more. As Hogan and Sathy note in Inclusive Teaching, “when used regularly, effectively, and not optionally, [polling] requires all students to synthesize material and apply it many times in a class session…Plus, the constant formative feedback tells both the student and the instructor what a student might need to practice more.” (Hogan and Sathy 2022, 130)

For more information about this tool, see our Autumn 2023 event, Taking the Temperature: A “Poll for Every Occasion” Poll Everywhere & Real-Time Feedback, date TBA.

Check for understanding using Canvas Quizzes

Like poll software, but better suited to use outside of class time, Canvas Quizzes are an excellent tool for concept clarification. And, with the new quiz engine in Canvas, instructors can use an even broader array of question types to engage students in more creative ways. From familiar question types like true or false and multiple choice to new types like sequence ordering and image hotspot selection, instructors have many ways to have students recall and apply concepts they’ve covered in a low-stakes setting.

In one of their simplest applications, Canvas Quizzes’ essay response questions offer an easy way to assign “minute papers,” a short activity that asks students to retrieve knowledge they’ve just learned, restate it in their own words, and even prioritize what they believe to be the most important details. Whether you’re asking students to undertake a quick application of an important concept as advocated for by Handelsman, or complete a quick “brain dump” for retrieval practice as described by Nilson (Nilson 2010), minute papers or “short writes” are an active learning exercise you can easily integrate into your teaching.

These are just a few ways that you can create opportunities for active learning with the help of UChicago teaching tools. For more ideas, watch our blog for more posts in this series, and consider joining us for Try IT: Academic Tech for Active Learning, our new series on infusing active learning into your teaching.

In our next post in this series, we will discuss the benefits of using microlectures, short videos covering discrete, important concepts as an alternative to lectures that cover a large amount of material in a longer, continuous block of time. Crucially, microlectures offer their greatest benefit when paired with active learning exercises.

Further Resources

- For a list of our office hours and upcoming workshops, please visit our workshop schedule for events that fit your schedule.

- For individual consultations, please send an email to Academictech@uchicago.edu.

Works Cited

Deslauriers, Louis, Ellen Schelew, and Carl Wieman. 2011. “Improved Learning in a Large-Enrollment PhysicsClass.” Science 332 (6031): 862–64. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1201783.

Handelsman, Jo, Sarah Miller, and Christine Pfund. 2007. Scientific Teaching. : Englewood, Colo. : New York: Wisconsin Program for Scientific Teaching ; Roberts and Co. ; W.H. Freeman & Co. https://catalog.lib.uchicago.edu/vufind/Record/11380889.

Hogan, Kelly A., and Viji Sathy. 2022. Inclusive Teaching: Strategies for Promoting Equity in the College Classroom. First edition. Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press. https://catalog.lib.uchicago.edu/vufind/Record/12775184.

Kalir, Remi, and Antero Garcia. 2021. Annotation. The MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. https://catalog.lib.uchicago.edu/vufind/Record/12661274.

Nilson, Linda Burzotta. 2010. Teaching at Its Best: A Research-Based Resource for College Instructors. 3rd ed. Hoboken: Wiley. https://catalog.lib.uchicago.edu/vufind/Record/10370070.