This three-part series explores a wide range of digital tools and pedagogical strategies that support writing instruction. The first post offered an approach to writing – and to writing instruction – as a process. This installment explores digital tools suited to the development and drafting stage of writing. For more, read part three, which includes ideas for workshops, feedback, and revision.

Starting from “Scratch”

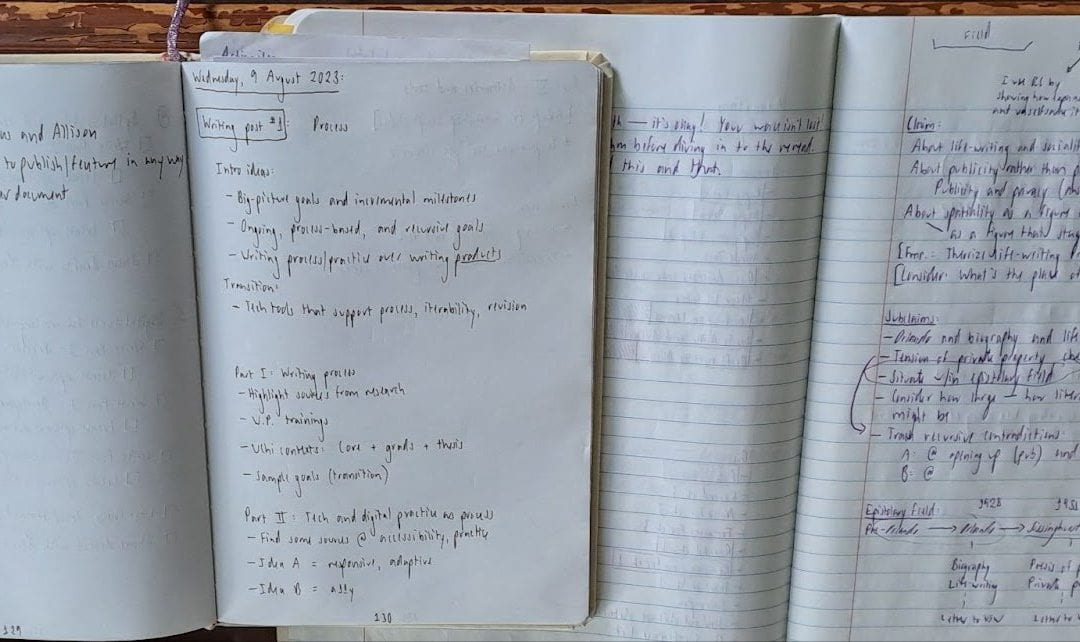

Whether you last entered an elementary school classroom as a student, teacher, parent, or assistant, you might recall one particular tool that represents an important turnstile through which young writers pass: “scrap paper,” also referred to as “scratch paper” or “rough paper.”

Scratch paper names both a material (a discarded sheet or scrap of paper available to students) and an activity (the process by which students brainstorm, plan, and sketch out the skeleton of a piece of writing). As students gain experience as writers, they move progressively from scrap-paper sketches to first, second, and final drafts of paragraphs and essays. In this post, we return to scratch paper – in all of its messiness! – as a workable model for the development and drafting processes of writing in the higher education classroom.

Despite its humble appearance, scratch paper can serve as a valuable pedagogical tool, challenging students to engage in sophisticated and rigorous tasks. Whether they are novice writers or advanced undergraduates and graduate students, writers can use scratch paper to:

- Clarify their starting position and intuitions

- Generate observations and supporting materials/reasons.

- Shape an idea, question, argument, or other forms of a “whole.”

- Experiment with different ways of connecting parts under the umbrella of that “whole.”

- Identify gaps in knowledge or areas that require further thought.

The primary distinction between writing at higher levels of education and primary/secondary education lies in the scope of assignments and the targeted audience, as opposed to the methods that can be used to produce quality work.

In this post, we’ll explore four key stages of development and drafting, and highlight specific digital tools that can aid students in each stage:

- Identifying a point of entry

- Generative pre-writing

- Managing sources

- Transitioning from pre-writing to writing

Identifying a Point of Entry

Finding an exciting topic or unusual question represents, in many respects, the most conceptually challenging aspect of any writing project. This is hard and uniquely human-thinking work that LLMs such as ChatGPT are unable to perform on a writer’s behalf.

Tailoring to the assignment’s scale, scope, and purpose, you may direct students to use provided syllabus materials or seek their own primary sources. Whether starting fresh projects or expanding previous work, annotation and collaborative brainstorming prove valuable for guiding students to specific entry points, aligning with diverse goals.

Annotation

Annotation offers a remarkable opportunity for students to engage with their insights, curiosity, and questions while reading. It encourages them to slow down, facilitating a deeper understanding of the material. In the context of topic development for writing, annotation fosters metacognitive skills, helping students notice and articulate their thoughts precisely within the text. Social annotation allows collaborative contributions and low-stakes conversations, while independent annotation challenges students to mark up readings, sources, and class notes autonomously.

Two especially effective tools for annotation available to UChicago instructors include Canvas Annotation Assignments (independent annotation) and Hypothes.is. For more on these two tools, check out previous ATS blog posts: Expanded Student Annotation Assignment Options in Canvas and Social Annotation and the Pedagogy of Hypothes.is.

Collaborative Brainstorming

Collaborative brainstorming encourages students to think laterally about course topics and materials, making space for unexpected intertextual and interdisciplinary connections. With streamlined digital tools, such as Canvas Pages editable by students, Google Docs, or Canvas Collaborations, you can invite your students to contribute to a shared bibliography, digital exhibit, or other gallery of ideas.

Generative Pre-Writing

Generative pre-writing, a sometimes overlooked stage, involves writers exploring subtopics, questions, and primary materials in an unstructured manner. This phase is comparable to musical “band noise” or jamming, where musicians experiment with chords, keys, and time signatures in an improvisational and investigative fashion. A useful approach to introduce a loose structure to this pre-writing phase is through a free-writing exercise.

When assigning a free-writing activity, striking a balance between openness and constraints is crucial. The term “free-” implies encouraging students to generate thoughts without the burden of editing or self-criticism. However, it’s essential to convey the purpose of free-writing and make constraints explicit. Introduce time-based constraints, like “Produce free-writing for 15 minutes in response to [X],” and consider allocating time segments to addressing specific points.

Additionally, clearly communicate clear expectations to students regarding how they will share their work. Specify whether to convey main ideas in bullet points or selected sentences and identify the intended audience— the instructor, TA, or peers in a writing group.

Two effective tools for free-writing exercises include Canvas Assignments and Canvas Discussions. These are intuitive for students when submitting work and streamlined for instructors when sifting through submissions. When selecting a tool, consider whether you’d like for free-writing to initiate peer-to-peer collaborations or whether you wish to provide feedback privately.

Managing Sources

Identifying, synthesizing, and managing sources is a critical component of writing development in higher education. Regardless of field or level, students should be constantly honing their capacity to identify, assess, and engage with sources and interlocutors.

Tracking those engagements is crucial – and the sooner students begin, the better. Our colleagues in the University of Chicago Libraries maintain excellent guides on citation and notes management tools, which are accessible on the Library website. Two tools they recommend include EndNote and Zotero, both of which offer free versions to students.

From Pre-Writing to Writing

When students shift from pre-writing to writing, they have already done a great deal of quality work: identifying and interacting with their sources; developing a sense of their own ideas; and shaping an argument. Making a shift into draft development entails harnessing their previous thinking and considering the audience. Two strategies for moving into draft development include idea workshops and proposals.

Idea Workshops

A collaborative approach to advancing into the draft development stage involves workshopping ideas in small groups. In this workshop, students should be encouraged to pose questions and offer connections that can assist the writer in the actual drafting process. When organizing a “topic” or “idea” workshop, clearly outline what you want students to share for feedback and additionally provide thorough explanations and models of effective feedback..

Canvas Discussions represent one digital tool that can support this micro-workshop activity. A second tool that’s particularly effective is Ed Discussion, a powerful digital discussion tool that enables students to create and participate in threaded conversations.

Proposal

Proposals can be a powerful tool that requires students to narrativize their writing project. After students have utilized lateral thinking and exploratory writing in the pre-writing phase, this can be a valuable next step. With a proposal, students gather the work they’ve generated and translate this into a narrative form that will be legible to an external reader.

When assigning a proposal, consider what you want your students to produce. What do you want to know about where their project is taking them? If a proposal is a map, what features and routes do you want students to take care to represent? These might include sources, subtopics, or questions.

Finally, prompt feedback is of the essence when assigning a proposal. Because proposals represent a bridge between prewriting and writing, keeping turnaround time brief is important. When choosing a digital tool or workflow, consider what will enable you to provide feedback most intuitively. One option we recommend is Canvas Assignments. After students submit proposals in the format you have specified, you will be able to easily sift through submissions using SpeedGrader and provide feedback via a text box, a file attachment (i.e. a Word document that you upload), or in a multimedia format (i.e. audio/oral comments).

Optimize the Writing Process

The journey from scratch paper to a well-crafted academic piece is a process that requires careful navigation through development and drafting. The four key stages we’ve delved into – identifying a point of entry, generative pre-writing, managing sources, and transitioning from pre-writing to writing – offer a comprehensive guide to foster effective writing practices.

Digital tools such as Canvas Annotation Assignments, Hypothes.is, and Ed Discussion, provide practical solutions to enhance collaboration, annotation, and idea workshops in the modern classroom. Embracing the strategies outlined in this article can help students navigate this journey with confidence, transforming their initial scribbles on scratch paper into well-articulated and compelling academic works.

Further Resources

- Academic Technology Solutions’ full list of Teaching Tools

- Get in touch with ATS through Office Hours or Consultations

- UChicago Grad Writing Resources

- The University of Chicago Writing Program

- Part One and Part Two of this Digital Tools for Teaching Writing series