Author’s Note: This is the latest installment in an ongoing series concerned with issues of academic integrity, particularly as they relate to classroom technologies. To view the previous installments, please see the Academic Integrity tag on our website. You are also encouraged to read the recent blog post on AI-resistant assignments from ATS instructional designer Michael Hernandez.

- Generative Content Tools: Beyond Text

- Tools and Techniques for the New World of Generative AI

- Getting Help

As we recently discussed in our blog post on ChatGPT and other generative writing tools, artificial intelligence (AI) is now a major concern for faculty, instructors, and support staff in higher education. AI has progressed by leaps and bounds within the last year, and it is now possible for a student to generate an entire reasonably coherent essay simply by giving a prompt to a generative writing tool such as ChatGPT. But this is only the tip of the iceberg. As Dr. Sarah Elaine Eaton, an academic integrity expert at the University of Calgary, explained in a recent webinar, other, more sophisticated AI tools for generating content are already here. In this post, we will examine some of these tools and their implications. We will then consider how faculty and instructors may best design authentic assessments so as to minimize the risk that students will turn to AI for dishonest behavior.

Generative Content Tools: Beyond Text

As the lion’s share of popular and scholarly attention has fallen upon tools to generate written text, researchers and programmers in generative AI have branched out to other content areas, especially that of visual imagery. Tools now available to a wide audience include:

- Midjourney, which can create customized images based upon a text prompt.

- Tome, which generates entire slide decks with both text and images from a prompt.

- Runway, a video creation tool.

- Elicit, a “research aid” that, when given a research question, trawls existing scholarly work and extracts information it deems pertinent to that question.

Even ChatGPT itself is being put to new applications beyond essay writing. Research suggests that it can fix bugs in computer code at least as well as, if not better than, existing machine learning models.

The very existence of such tools raises important questions. Some ethicists and scholars of intellectual property (IP) law have argued that these models are a form of IP theft, relying as they do upon text, images, and so on that were originally created by others. OpenAI, makers of ChatGPT, and their corporate investor Microsoft have been sued for allegedly monetizing open-source computer code. Many artists, too, are pushing back against AI art from platforms like Midjourney and DALL-E.

A related question: can an AI genuinely be said to be the “author” of the content it creates? This matter is not merely academic: already some researchers using Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT are citing them as co-authors of the resulting papers, despite the objection that an AI cannot assume ethical responsibility for its content or defend it in a public forum.

These are problems too great to be addressed here. We shall focus instead on a more immediate concern: in a world where students can generate PowerPoint presentations, YouTube videos, and the like from a single sentence of text, how can faculty and instructors reduce the chances of AI-based cheating?

Tools and Techniques for the New World of Generative AI

Like its predecessor, this post makes no claims to offer definitive answers, if definitive answers are even possible at this stage. What follows should be understood as tentative, and our advice will evolve along with the spread and evolution of AI tools themselves.

The Course Level: Set Expectations and Clarify Learning Goals

If students are to be deterred from taking the easy route, it is vital that they understand the desired outcomes of your course, as well as how the assessments they are completing further those outcomes. There are several methods that can help achieve this.

- Place language in your syllabus on the use of AI tools. At Texas State University, which has a student honor code to manage academic infractions, the honor council provided all faculty members with language and resources on the implications of AI for academic integrity. The language reads, in part: “Our institution, teaching and evaluation methods, and follow-on industry rely on the use of computers to assist with common work tasks every day. However, when used in lieu of individual thought, creation, and synthesis of knowledge by falsely submitting a paper written (all or in part) as one’s own original work, an academic integrity violation results.” If you have a digital syllabus in Canvas, not only can you include such language at the beginning of the quarter, but you can also adapt the syllabus easily as the course goes on to adjust to rapidly changing circumstances.

- Use Canvas Rubrics and Canvas Outcomes to make learning goals clear. Both Canvas Rubrics and Canvas Outcomes allow you to clarify how assessments contribute to the overall goals of your course. Rubrics are assignment-specific and can be used to lay out the criteria by which a submission will be graded, so that students can better understand what you are looking for: are the mechanics of writing foremost, for example, or is originality of thought more important? Outcomes, meanwhile, can be connected to multiple assessments in Canvas, making it possible both for you to track students’ progress across the various competencies and for them to see that the work you are assigning has a purpose. As with AI tools, so in general, highly motivated students are less likely to resort to dishonest methods.

The Assessment Level: Create Authentic Assessments

There are also steps you can take at the level of individual assessments to make AI-facilitated academic dishonesty less likely.

- Promote close reading with Hypothesis. Hypothesis, a digital tool for collaborative annotation, is designed to help students drill down into a text. It also promotes the collective construction of knowledge, as students respond to each other’s annotations and ask questions that can further discourse. Not only can the use of Hypothesis make reading a more engaging activity, but it also builds the vital skill of extracting information from a text. This may help to make your students less dependent on Elicit and similar tools that (purport to) do the heavy lifting of information-gathering for them.

- Teach students citation management. Endnote and Zotero are two UChicago-supported tools for managing citations. Unlike Elicit, however, they rely on the student’s own judgment to decide what material is worth citing. As part of a more general program, wherein you explain to your students not only how to cite, but also why citation is vital, these tools can help them to do the intellectual spadework of building a bibliography without being dependent on AI. (To learn more, please see the Library’s Teaching and Learning page.)

- Promote metacognition with Canvas Quizzes. There are many uses for Canvas Quizzes – quick concept checks, timed exams, etc. – but a use you may not have considered is the reflective exercise to promote metacognition (thinking about thinking). When students have a chance to better understand their own thought processes, they may also gain a better understanding of the difference between their thinking about a topic and the “thinking” of an information-agglomerating AI. In turn, this can help them to be more engaged and more interested in expressing their knowledge themselves, rather than relying on AI tools to be their “voice”.

- Make videos active. Both Canvas and Panopto offer mechanisms to encourage discussion around videos. You can have your students embed videos they create in Canvas discussion boards, or you can use Panopto’s Discussion function to have a timestamped discussion on the video itself. A student who has generated a video using a tool like Runway will be hard-pressed to explain its content in detail in such a discussion format, and it will also help your students feel that video creation is only part of a broader collaborative knowledge process, which will help keep them engaged.

- Assign students to create a podcast. Podcasting assignments are an excellent way to help students express themselves meaningfully. What’s more, it is much more difficult to fake a podcast with AI – particularly if it happens to be in interview format – than to generate an image or a video. With a personalized assessment (e.g. “Talk about your experiences growing up in X country”), students will be both less inclined to cheat and less able to cheat. (For more information, please see our 2021 Symposium session on Presenting Research Digitally.)

As a general rule, an engaged student is less likely to behave dishonestly; a disengaged student, more likely. Thus, all the tools and techniques enumerated above should be put to one overarching use: making your students feel that the course material matters. That is a more powerful defense against cheating than any technology.

Getting Help

If you have further questions, Academic Technology Solutions is here to help. You can schedule a consultation with us or drop by our office hours (virtual and in-person, no appointment needed). We also offer a range of workshops on topics in teaching with technology.

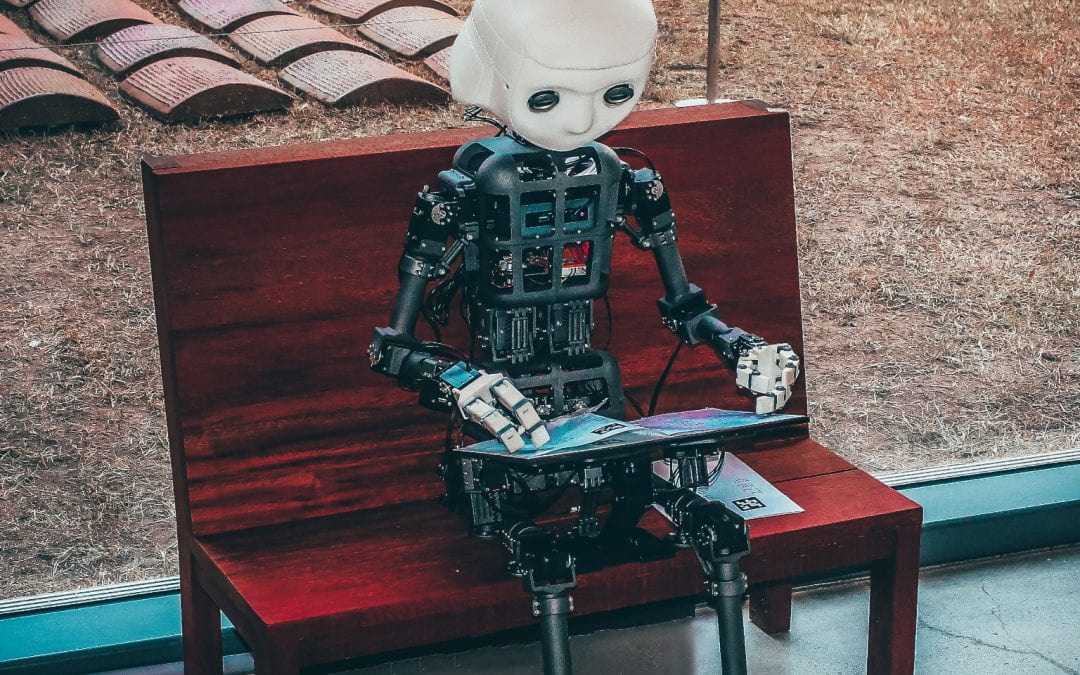

(Cover photo by Andrea De Santis on Unsplash)